Chapter 7

Daguerreotypes, Ambrotypes, and Tintypes

This chapter discusses Daguerreotypes, tintypes, ambrotypes, and ambrotype derivatives Hallotypes, Diaphanotypes, spherotypes, and alabastrines.

Specimens of Daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes are

sometimes mistaken for each other in similar decorative cases.

Daguerreotypes and ambrotypes were always cased; only tintypes

were both cased and uncased. When cased, tintypes resemble

ambrotypes on cursory inspection. The normally rather obvious

differences in the three types are often obscured by

deterioration and by original process variations. Unlike paper

photographs, however, these three types did not fade. It took

many years to recognize and control impurities in paper and

gelatin, and in processing chemicals.

Daguerreotypes

The literature on Daguerreotypes is phenomenal in physical

volume and in the vitality of modern research. Virtually all

photographic history books contain accounts of the invention

and worldwide acceptance of the process from about 1840 to the

mid 1860's. The calotype made only minor inroads in its

popularity, even though the calotype negative permitted

duplication, while the Daguerreotype had to be rephotographed

or etched and inkprinted. The wet collodion and tintype

processes finally superseded the Daguerreotype, but it left a

rich legacy of some of the earliest historical photographic

images.

Besides the standard history books, Gernsheim [61], Barger [8],

and Newhall [104] have separate histories of the Daguerreotype,

based on historical and cultural factors. The process has been

revived in recent years, notably by Irving Pobboravsky of the

Rochester Institute of Technology, with beautiful results.

Romer [126] estimates that there are or have been several dozen

modern practitioners of the art.

The Daguerreotype has been studied more extensively by modern

analytical methods then any other historical photographic

process. Most of the results to date are listed in the

bibliography under Modern Scientific Studies. The definitive

work has been reported by M. Susan Barger and her collaborators

[references 7 through 18]. In particular, Barger and White,

reference 15, is a work of major significance, not only

regarding the Daguerreotype but also parallel branches of

photography in that period. Other work is by Pobboravsky [118

and [119], Swan et al [138], and Jacobson & Leyshon [80]. A

scientific model is described by Barger [8 and 12]. Modern

scientific interest in the process is aroused by its embodiment

of thin film physics and optics. It is the only completely

inorganic chemical photographic system with no emulsion, which

makes it an interesting model for photosensitive research.

Daguerreotypes are probably the easiest of the three cased

types to identify because the polished silver exhibits specular

reflection. This means that they are silver mirrors in which

the viewer can see a true image reflected, not just a metallic

sheen. The appearance depends critically on the viewing

angle.

The nature of the Daguerreotype image is shown in scanning

electron micrographs in Appendix I. Highlights in the image

contain a high density of light - scattering amalgam particles,

so that some incident light has a good probability of reaching

the viewer's eye. Shadows have fewer such particles, so

incident light is efficiently reflected away from the eye

unless the viewing angle is very close to ninety degrees. In

the latter case, the viewer will see his or her own image.

The polished silver is a property unique to Daguerreotypes and

a valuable aid to recognition, but there are two problems.

First, the silver is subject to tarnishing, especially around

the edges as shown in Figure 5. Second, all Daguerreotypes have

protective glass over the picture, and reflections from the

glass can be mistaken for reflections from the silver. This may

confuse identification because all ambrotypes and some tintypes

were also glass covered.

|

| Figure 5 |

Daguerreotypes were made in standard sizes (not all

authorities agree on these sizes):

|

Table 2

|

|

| Whole plate | 6-1/2 x 8-1/2 inches |

| Half plate | 4-1/4 x 5-1/2 |

| Quarter plate | 3-1/4 x 4-1/4 |

| Sixth plate | 2-3/4 x 3-1/4 |

| Ninth plate | 2 x 2-1/2 |

| Sixteenth plate | 1-3/8 x 1-5/8 |

In addition, there was a "double whole plate", also called

Mammouth or Imperial plate, 10 1/2 x 13 1/2 inches. This was

the largest Daguerreotype size ever made, and a few were made

about 1850. According to Condax [35] no camera capable of

holding these plates is known to exist today.

Most Daguerreotypists bought whole plates and cut them to

desired sizes, using much ingenuity to minimize waste. Rough

cut edges and corners are common, concealed in the cases. Blank

plates were supplied to the trade, mostly from French and

American sources, and were made by two processes: (1)

electroplated silver on copper, and (2) cladding.

Cladding was discovered about 1742 by Thomas Boulsover. It is a

process of fusion bonding by alloying a bar of silver against a

bar of copper and running them together through a rolling mill

under great pressure. The process is described in Bisbee [23].

The silver thickness of clad plates was one-fortieth to

one-sixtieth of the copper thickness; the number 40 was often

stamped in one corner of whole plates. Clad plates were used

for the earlier Daguerreotypes, while electroplated plates were

later used by some Daguerreotypists.

Electroplating was patented in 1840 and put into practical use

about 1844; it depended on the availability of electric

current. 'Galvanic' batteries were used as a power source, and

electroplated plates were called 'galvanized' (modern usage of

the term refers to hot-zinc dipping). Pobboravsky [119, 42]

states that French electroplated Daguerreotype plates were made

as early as 1851, with an embossed hallmark of the process.

The microstructure of the silver surface is different in the

two processes. Rolling generates minute longitudinal marks,

while electroplating produces a more porous grain structure

which can be seen microscopically. Fusion bonding also produces

some alloying of the copper in the silver, which varied with

process parameters. In principle it should be possible to trace

the source of a plate by analysis of these characteristics.

Both processes are common metallurgical operations today.

The sensitized plates were exposed directly in the camera,

generating a reversed image (see Chapter 11), but not quite all

Daguerreotypes are reversed. Some are rephotographed copies, so

that shop signs, for example, read normally. Others were made

by photographing through a 45 degree prism mounted in front of

the camera lens, or from a mirror. Both of these techniques

produced a normal picture but were not often used because they

were too much trouble and expense. People were so entranced

with the novelty of fixed images that it didn't really matter

if portraits were reversed.

There have been several published processes in the past few

years for removing tarnish from Daguerreotypes. It is strongly

recommended that none of them be used without first reviewing

the most recent techniques: see the comments in Chapter 12 and

Appendix I. Cosmetic reasons are not sufficient to justify the

risk of irreversible loss of image information.

Ambrotypes

Ambrotypes were more popular in America, appearing from 1854

until about 1865; their European name was amphitype. They are

collodion negatives (not positives) on glass, sandwiched

against dark background materials in a case. They appear as

positives for the following reason. When any transparent silver

based negative is viewed from either side, a small amount of

light is reflected back to the viewer from the shadows;

essentially no light is reflected from the highlights. This is

difficult to verify in a brightly lighted room because so much

light comes through the negative, but it can be seen in a

darkened room with the illumination coming from behind the

viewer. If a matte black surface is placed behind the negative,

it will prevent any light from coming back to the viewer from

the clear regions, transforming them into shadows. Light will

still be reflected from the darkened areas of the negative and

they become highlights relative to the clear areas. Thus the

negative now appears as a positive, though not very bright or

contrasty by modern standards. Daguerreotypes were usually not

very contrasty either, so ambrotypes became competitive,

especially since they were cheaper.

Ambrotypes often look like they were made on a dark and stormy

night. Efforts were made to improve the contrast; exposure and

development techniques were optimized, and tinting helped to

relieve the dullness. Different kinds of background were used;

japanned black cardboard, velvet, black varnished metal, and

black varnish applied directly to the collodion negative.

Towler [108, 138] lists four varnish formulations that could be

applied to either side of the glass negative. If it was applied

to the collodion side the picture was not reversed to the

viewer but it was duller than if the glass on the side opposite

the collodion was varnished. Most ambrotypes are reversed as a

tradeoff for a slightly brighter appearance.

Varnish on the glass is often blistered after a century and a

quarter; in such cases the picture appears hideous and

apparently worthless, but there is hope of restoration. The

picture can be restored by removing the old lacquer; this is a

task for a skilled restorer who knows which solvent will remove

the varnish and not the collodion picture. Black paper

(acid-free archival quality) will then restore the picture if

the collodion image is intact. Sometimes just placing black

paper against the blistered varnish will improve the

appearance, but it is not a proper restoration and it may

abrade the collodion if that is the side that was varnished.

Neither Daguerreotypes nor tintypes show this particular form

of deterioration, so blistering is at least an aid to

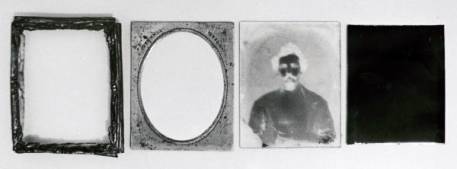

identification. Figure 6 shows an the component parts of an

ambrotype that is backed with a piece of black lacquered iron

with formed raised edges to prevent close contact with the

glass. The collodion surface can thus face the backing without

abrasion damage, and the picture is not reversed. This backing

has survived without deterioration. The image photographed on a

white background can be seen to be a negative.

|

| Figure 6 |

|

|

| Figure

7a |

Figure 7b |

Note that in paper processes, shadows (not highlights) are

rendered by heavy silver deposits in the negative, and positive

prints are produced in a second step from negatives. Highlights

in paper prints derive their color from the underlying paper

stock.

Some tintypes are very dark overall while other specimens have

surprisingly good contrast with an almost white background that

is independent of viewing angle. Crawford [38, 43] mentions

that a grayish white background could be created by adding

mercuric chloride or nitric acid to the developer. Neither Eder

nor Towler mention this process, but there are striking

variations in the contrast range of different specimens, for

which we have been unable to establish a date correlation. The

tricks used by individual practitioners often interfere with

hopes of finding a convenient historical progression for

dating.

Tintype plates, like Daguerreotypes, were exposed directly in

the camera and therefore were reversed, but again there are

exceptions. In addition to copying, and the use of prisms or

mirrors, the collodion image could be transferred to another

metal plate. The resulting picture was called, naturally, a

transferotype and was rereversed, or normal. Further, the final

metal base did not have to be japanned iron and the magnet test

fails if it is, for example, copper or brass. These exceptions

are relatively uncommon (we have no frequency data), but the

serious historian should be aware of the possibilities.

Estabrooke's book [51] contains inserted 'non-reversed'

tintypes "made by the identical processes offered in this

book", but he fails to describe the 'non-reversal' process.

However, he describes the 'copy stand' in his darkroom and it

can be inferred that it was used. If he had used a prism at the

camera lens (see Chapter 11), one would have expected him to

mention it in his detailed description of his 'glass room', or

studio.

The collodion surface of tintypes often shows fine crazing or

cracking, which distinguishes them from ambrotypes. Remarkably,

many tintypes show no trace of rust in spite of bends and

scratches. At one time it was fashionable to adorn tombstones

with tintypes, and a few have survived a century of outdoor

exposure.

Tintypes were made in many sizes with little standardization.

The largest was 6-1/2 x 8-1/2 inches. The base material was

cheap and many tintypes are very roughcut and irregular. Some

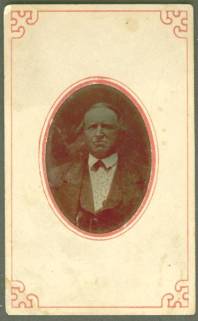

were mounted in Daguerreotype or ambrotype cases; they can

usually be identified with a small magnet. Tintypes were often

glued on small paper mounts or mounted as cartes-de-visite. The

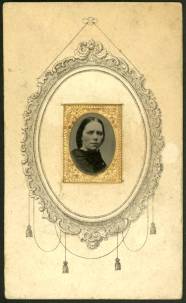

tiny Gem tintypes (1 x 1 3/8 inch - see Figure 8) were

sometimes mounted in stamped brass frames that resembled

Daguerreotype frames; these frames were then crimped on

cardboard mounts. But the majority of tintypes were simply

unmounted; in this form they could be mailed easily and

cheaply, making them popular during the Civil War.

|

|

| Figure 8 |

Many tintypes are rather grubby in appearance, as Crawford

aptly describes them, and art critics universally turned up

their noses. Aesthetically they were no match for the elegant

platinotype. But they are durable and unfaded after more than a

century, and today they remain a plentiful legacy of the

appearance of Civil War soldiers, celebrities, period clothing,

and architecture.

Direct Positives

Daguerreotypes and tintypes were direct positives and were

commercially very successful, even though they lacked an

intermediate negative for reproduction. Many inventors strove

for the simplicity of single step positive processes and there

were some successes. But why does a light-struck area of the

sensitive surface appear light after processing in spite of the

earliest observations that silver salts darken when exposed to

light?

In both tintypes and Daguerreotypes, the light from highlights

in the subject produces a chemical change in the sensitive

surface. In the Daguerreotype, nucleation centers in the

highlights are converted to dense concentrations of

mercury-silver amalgam particles. These particles scatter more

reflected light to the viewing eye than does the surrounding

area with no particles, resulting in a "positive" image. In the

tintype there are no amalgam particles, but the reduced silver

particles in the highlights are more reflective than the dark

backing without silver particles exposed in the shadows. Both

processes relied upon the difference between reflectivity from

the highlights and from the shadows: there was a better chance

of light reaching the viewer from the highlights than from the

shadows.

Neither process worked on white paper, and both processes were

marginal in their contrast control compared with modern

processes.

Japanning

A description of japanning is in order, since it is rarely

described in photographic histories. Perry [111, 18] has a

useful description. Essentially it consists of baked lacquer,

usually applied in multiple layers to sheet iron, and baked

between each coat. The composition of early lacquers was

sometimes a trade secret, but Estabrooke's formula is simply

asphaltum (tar) in linseed oil. Tar is available from many

sources in nature, with variations in impurities, and japanning

quality was no doubt correspondingly variable. In Europe

japanning dated to the early 17th century, and in the East much

earlier. The original motivation was decoration, but it also

formed a very durable and rust-resistant coating that compares

favorably with some of our modern polymers.

Collodion images were sometimes printed or transferred (these

were two separate processes) on to japanned cardboard or

leather. In these cases the finish was air dried black varnish;

Towler [145, 150] has a simple recipe. True japanning requires

high temperature baking cycles that could not be used on

flammable materials, but many black varnishes or lacquers

acquired the generic term of japanning. For restoration

purposes it is not safe to assume resistance to any particular

solvent.

Japanned lacquer was produced in various colors besides black;

only the "chocolate" plate, patented in 1870, became as popular

as the black, and there are many surviving brown specimens. The

brown color was thought to be more lifelike; the same thinking

may have accounted for the popularity of sepia paper prints.

But gold or sepia toning was widely used on paper prints to

combat fading, so public acceptance of brown may have been a

factor. Tintypes and ambrotypes did not fade unless they were

grossly underfixed or washed, whereas paper prints suffered

chronically from fading problems for many years.

Tintype Nomenclature

Tintypes, the name most often used today, were also called

Ferrotypes, Melainotypes, Melanotypes, Melaneotypes,

Ferrographs, Adamanteans, Adamantines, and several other trade

names (see Estabrooke, [51]. These names reflect minor trade

differences, but they are all collodion-silver images on

japanned iron. The evolution of the many trade names is

complicated and illustrates the problems of assigning a single

identity to what now appears to us a single process. The

following account is largely paraphrased from Estabrooke's 1872

book [51].

Smith's invention is usually dated as 1854, but the date of

publication of his patent is February 19, 1856. Smith called it

the Melainotype, and Estabrooke says it was based on a French

invention of a black enamelled plate "for photographic

purposes" called the Melanotype plate. Apparently Smith's

contribution was to coat the Melanotype plate with collodion

containing a solution of silver salts.

Peter Neff bought Smith's Melainotype patent in 1856 (Eder says

1857) and continued manufacture for several years. At about the

same time (1856) Mr. V. M. Griswold of Peekskill New York

introduced his Ferrotype plates in defiance of Smith's (now

Neff's) patent. By this time the market was a free-for-all of

competing processes and tradenames, and one writer, in disgust,

referred to the various processes as 'hum-bug-otypes'. This

same writer favored the Melaneotype (sic), adding a new name to

the confusion. Some other tradenames were Adamantean, Phoenix,

Vernix, Eureka, Excelsior, Union, Star Ferrotype - all

collodion silver on japanned iron. Finally in 1870 the Phoenix

Plate Company introduced the "chocolate" plate which was a

sensation, short lived because the advent of chlorobromide

paper was imminent. Estabrooke remarks that "...in those times

every unimportant change was called a new process."

Mr. Griswold issued a rather plaintive statement concerning the

many trade names:

"Many other names have been given to similar plates, such as

Adamantine, Diamond, Eureka, Union, Vernis, Star Ferrotype,

Excelsior, and others, among which the most senseless and

meaningless is 'Tintype'. Not a particle of tin, in any shape,

is used in making or preparing the plates, or in making the

pictures, or has any connection with them anywhere, unless it

be, perhaps, the 'tin' which goes into the happy operator's

pocket after the successful completion of his work. None of

these names, however, have been considered so apt and

appropriate as Ferrotype, and it will, doubtless, be generally

accepted as long as the pictures are known." Alas, Mr.

Griswold, for your optimism.